SPARQL Query Guardrails: Making Your SPARQL Queries ETL-Ready

SPARQL is a powerful query language.

Its core concepts are basic and extended triple patterns. You can think of a triple pattern as a stencil: the cut-outs correspond to the variables in the pattern, while the solid areas represent the constants. Evaluating a query is like placing the stencil over the data graph and returning the pigmented vertices and edges.

SPARQL, by design, allows you to express arbitrary combinations of graph patterns and is entirely data-driven. A SPARQL query engine performs no semantic inference over the stencil you define; it simply evaluates patterns and returns the nodes and edges that match them.

As a result, a query can be syntactically valid, executable by any compliant engine, and even return results, while still being semantically meaningless with respect to the underlying data model. (I recently posted about this on LinkedIn, and I’m still looking for feedback if you have a moment to spare.)

That said, SPARQL does not know your intent, it only knows triples. A typo in a property may not fail, a misunderstanding of class relationships can still produce results, and a query can look perfectly reasonable while quietly violating the ontology.

In production graph platforms, especially those feeding downstream systems through ETL pipelines or supporting decision-making workflows, this weakness is a real potential point of failure. At gdotv, we treat this as a platform responsibility, not a user mistake.

In this post, I’ll introduce you to Query Guardrails in gdotv: a system that makes SPARQL safe, predictable, and industrial, without reducing its expressive power. Let’s begin.

A Running Example from the Life Sciences

To show how a SPARQL query can fail semantically, we’ll use a deliberately small healthcare and life sciences dataset, included below. This dataset is small enough to reason about completely, yet realistic enough to fail in meaningful ways:

@prefix ex: <http://example.org/> .

@prefix rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> .

@prefix rdfs: <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#> .

@prefix owl: <http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#> .

ex:Patient a rdfs:Class .

ex:Disease a rdfs:Class .

ex:Drug a rdfs:Class .

ex:Gene a rdfs:Class .

ex:Protein a rdfs:Class .

ex:Protein owl:disjointWith ex:Gene .

ex:hasDisease a rdf:Property ;

rdfs:domain ex:Patient ;

rdfs:range ex:Disease .

ex:treatedWith a rdf:Property ;

rdfs:domain ex:Disease ;

rdfs:range ex:Drug .

ex:targetsGene a rdf:Property ;

rdfs:domain ex:Drug ;

rdfs:range ex:Gene .

ex:encodedBy a rdf:Property ;

rdfs:domain ex:Protein ;

rdfs:range ex:Gene .

ex:interactsWith a rdf:Property ;

rdfs:domain ex:Protein ;

rdfs:range ex:Protein .

ex:Alice a ex:Patient ;

ex:hasDisease ex:Diabetes .

ex:Diabetes a ex:Disease ;

ex:treatedWith ex:Metformin .

ex:Metformin a ex:Drug ;

ex:targetsGene ex:AMPK .

ex:AMPK a ex:Gene.

ex:TP53_Gene a ex:Gene ;

rdfs:label "TP53" .

ex:TP53_Protein a ex:Protein ;

rdfs:label "TP53" .

ex:TP53_Protein ex:encodedBy ex:TP53_Gene .

Loading the Dataset in a Triplestore

I personally use a local instance of Apache Jena Fuseki for small graphs on my MacBook. Jena is open source, its Docker installation and binary distributions are secure and straightforward, and it provides a clean web interface that allows me to manage multiple independent datasets on a single local server.

Let’s walk through the steps to load the dataset into Apache Jena Fuseki.

- First, I create a new dataset called

life-science, then import the triples above as a simple.ttlfile. See the video below for an example walkthrough.

- Then I set up a new connection in gdotv with a simple query and a schema view. I can immediately verify that the dataset is loaded and ready to use. Watch the video below to see how I do it.

If you’re interested in trying out these SPARQL queries for yourself – and the query guardrails that alert you to their errors – download gdotv to follow along.

SPARQL Query Guardrailing

Now our dataset encodes a clear semantic chain that happens in an arbitrary life sciences context: Patient, Disease, Drug, Gene. We can now discuss how SPARQL can go wrong.

A Simple Triple Query: Looks Right, But Is Wrong

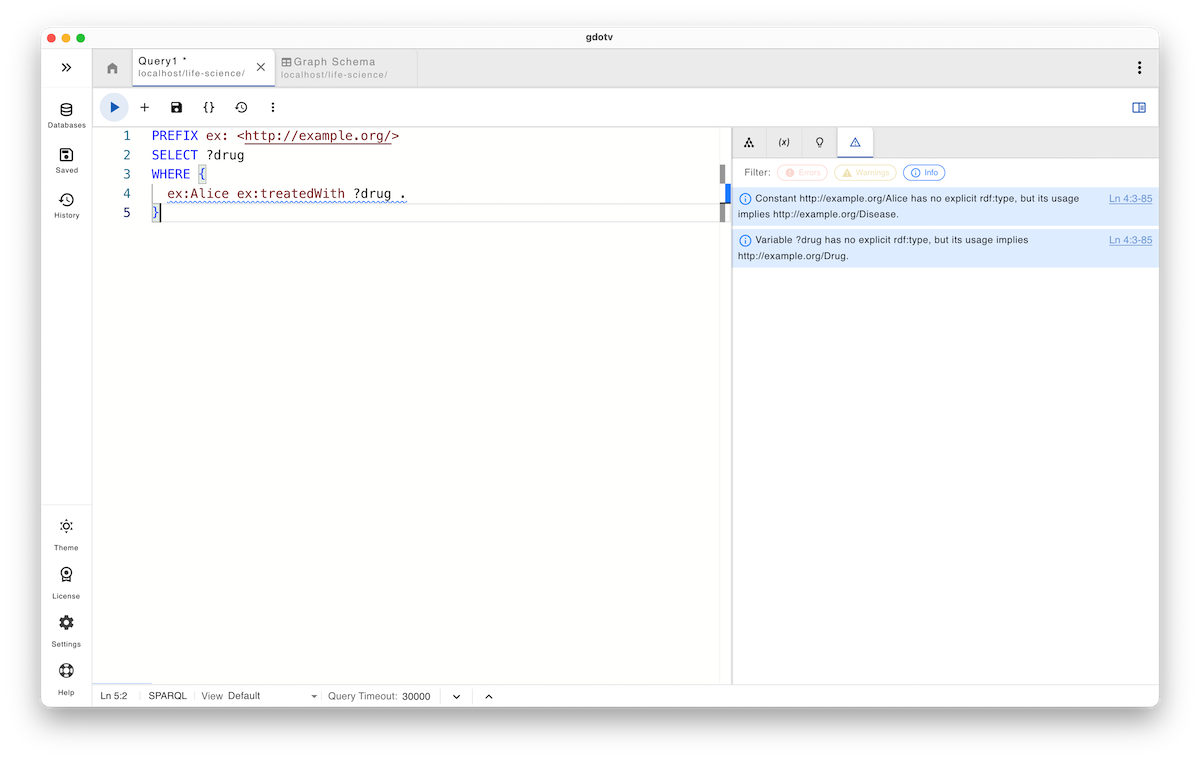

For our first example, we consider the following query:

SELECT ?drug WHERE { ex:Alice ex:treatedWith ?drug . }

Semantically, the user’s intent is obvious: “Which drug is Alice treated with?” The query is syntactically valid, and the SPARQL engine executes it without complaint. However, it returns no results.

The issue is not syntactic but semantic. According to the ontology, the predicate ex:treatedWith applies to a Disease, not to a Patient. In other words, the query connects Alice directly to a treatment relationship that is not defined for her type.

In gdotv, the query guardrails surface this problem before execution and even while the query is being written, giving you immediate, context-aware guidance. The system correctly infers that, given the predicate used, the subject position implies a Disease, while the query supplies a Person. This is not pedantry; it is a meaningful semantic mismatch:

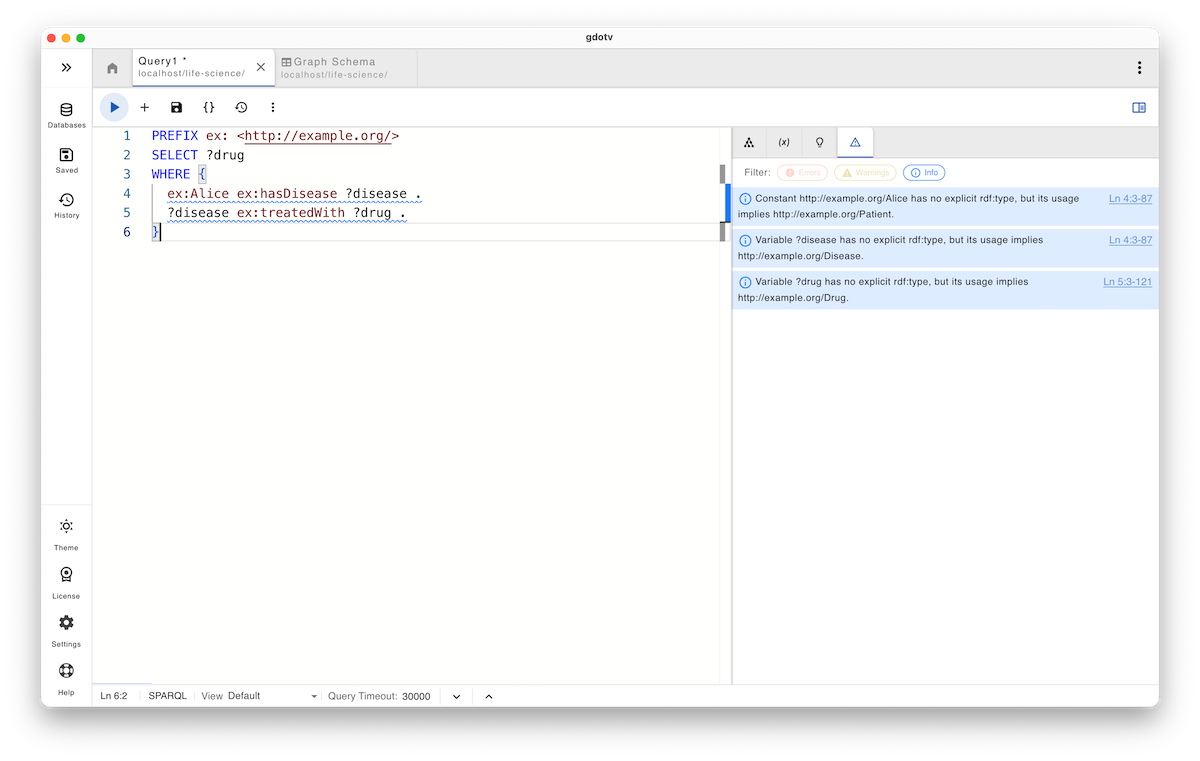

Once this mismatch is made explicit, the correct intermediate path becomes clear:

SELECT ?drug

WHERE {

ex:Alice ex:hasDisease ?disease .

?disease ex:treatedWith ?drug .

}

Here, every constant and variable appears in its proper semantic role, and the query now faithfully reflects the original intent:

Although this is a simple example, the same pattern frequently occurs deep inside complex queries, where empty result sets can remain hidden and extremely difficult to diagnose. With SPARQL query guardrails in place, identifying and fixing such issues becomes a straightforward sanity check rather than a debugging exercise.

Non-Existent Types & Nested Blocks (Object Nodes)

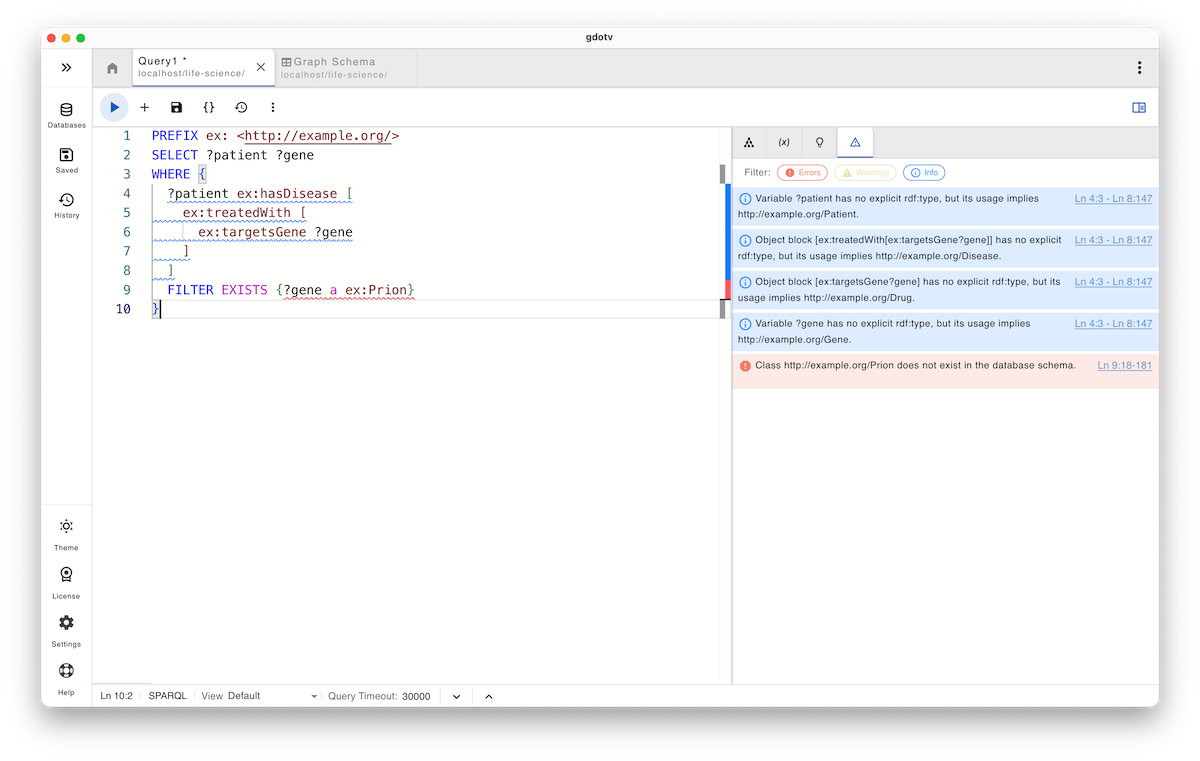

Now let’s look at a more complicated SPARQL query with a couple of nested object node clauses:

SELECT ?patient ?gene WHERE { ?patient ex:hasDisease [ ex:treatedWith [ ex:targetsGene ?gene ] ] FILTER EXISTS {?gene a ex:Prion} }

This is syntactically valid and will be accepted by any SPARQL engine, but it introduces a different class of semantic risk. The class ex:Prion does not exist in the ontology, yet it is used inside a FILTER EXISTS clause without any immediate execution failure. This can silently invalidate the query’s intent or turn the filter into a no-op, depending on the data, making the issue difficult to detect.

At the same time, the query relies heavily on nested blank nodes, which obscure the semantic roles of the variables involved.

Even though no explicit rdf:type is stated for the subject of ex:targetsGene, its usage within the pattern implies a ex:Drug, based on the predicate’s domain. The query guardrails surface both issues: they warn about the use of a non-existent class in the ontology and infer the semantic roles of each block, clarifying the expected types of intermediate nodes and variables.

Note that these hints from gdotv do not prevent the query from being submitted, nor do they force the addition of explicit types. Instead, they provide visibility into how the query will be interpreted semantically, allowing the author to make informed decisions before execution.

This guidance allows you, as the query author, to spot missing or invalid ontology terms and verify that inferred roles align with the intended data model before the query is executed.

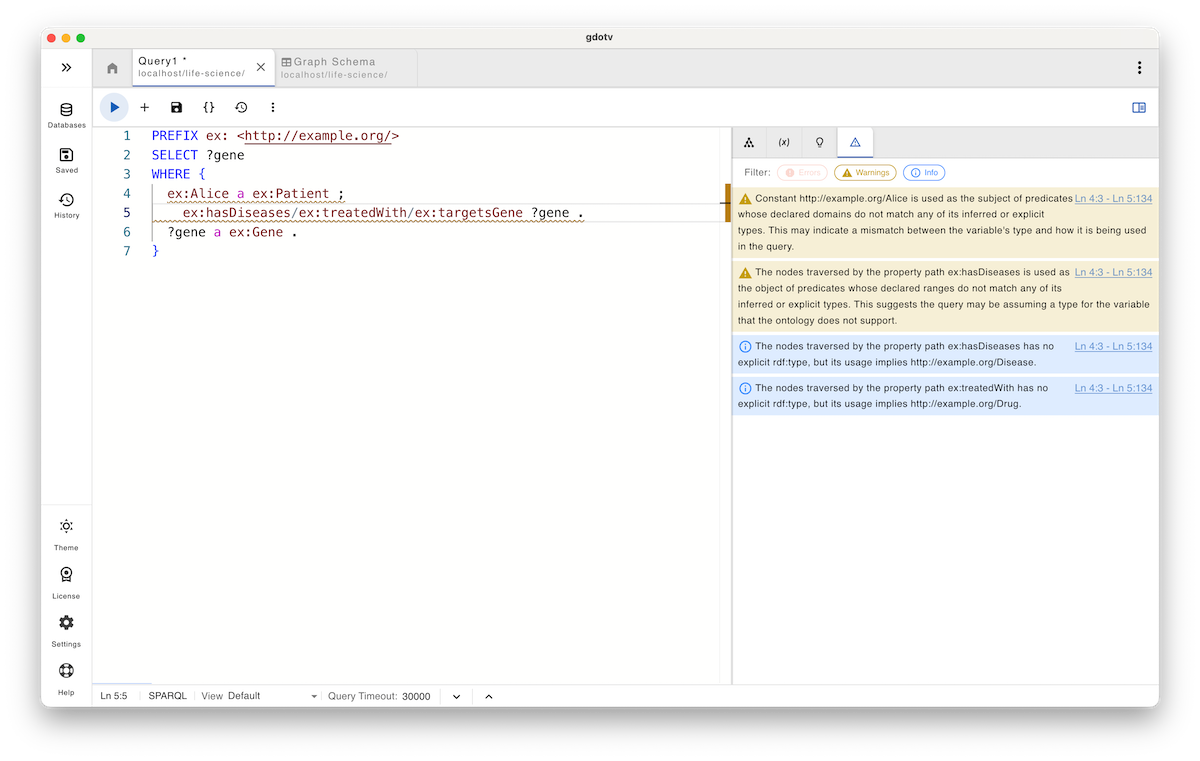

Property Path Queries: Expressive & Dangerous

SPARQL property paths are powerful abbreviations and, for that very reason, easy to misuse.

Consider the following query:

SELECT ?gene WHERE { ex:Alice a ex:Patient ; ex:hasDiseases/ex:treatedWith/ex:targetsGene ?gene . ?gene a ex:Gene . }

This SPARQL query is an elegant formulation that skips three intermediate variables, but it also hides several assumptions. Each segment of the path must be semantically compatible with the next, and the intermediate nodes must satisfy the expected domain and range constraints. In larger query spaces, this becomes especially error-prone, and extra care is required when mixing sequences with alternatives.

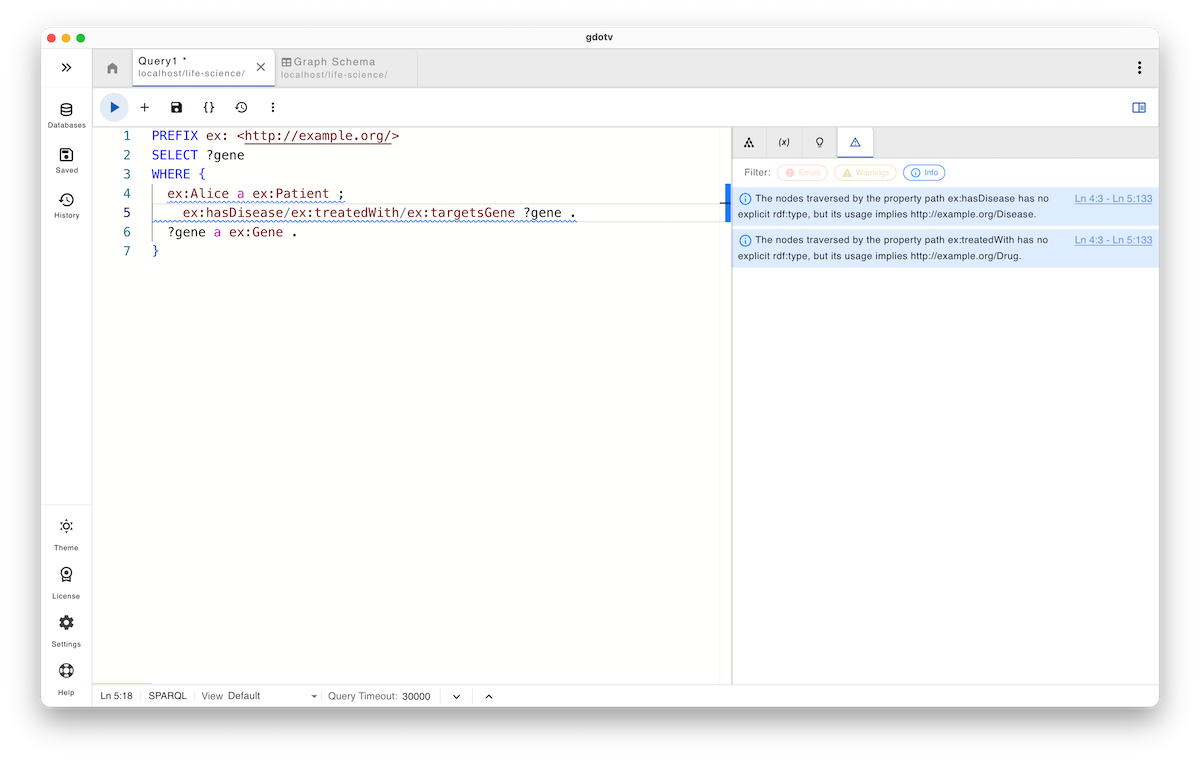

In this example, an intentional typo is introduced: ex:hasDiseases instead of ex:hasDisease. If submitted as-is, the query is syntactically valid and will be accepted by any compliant SPARQL engine. However, with gdotv’s query guardrails, warnings are raised immediately.

As shown, gdotv decomposes the property path into its individual steps and validates each one against the ontology, checking domain and range compatibility as well as consistency between consecutive segments.

In this case, the guardrail system flags that Alice is being used as the subject of a predicate whose domain does not match her type. A corresponding warning is also raised for the object position of the same pattern, where the inferred range is incompatible with the traversed node.

These warnings indicate that a predicate is being used that does not belong to any of the explicit or inferred types in the query. The guardrail system infers potential subject and object types from the surrounding patterns and considers them alongside explicit type assertions (for example, those introduced via rdf:type or a).

Since Alice is explicitly typed as a Patient, the system correctly concludes that an invalid or missing predicate is being used. Then, after fixing the typo, everything seems normal:

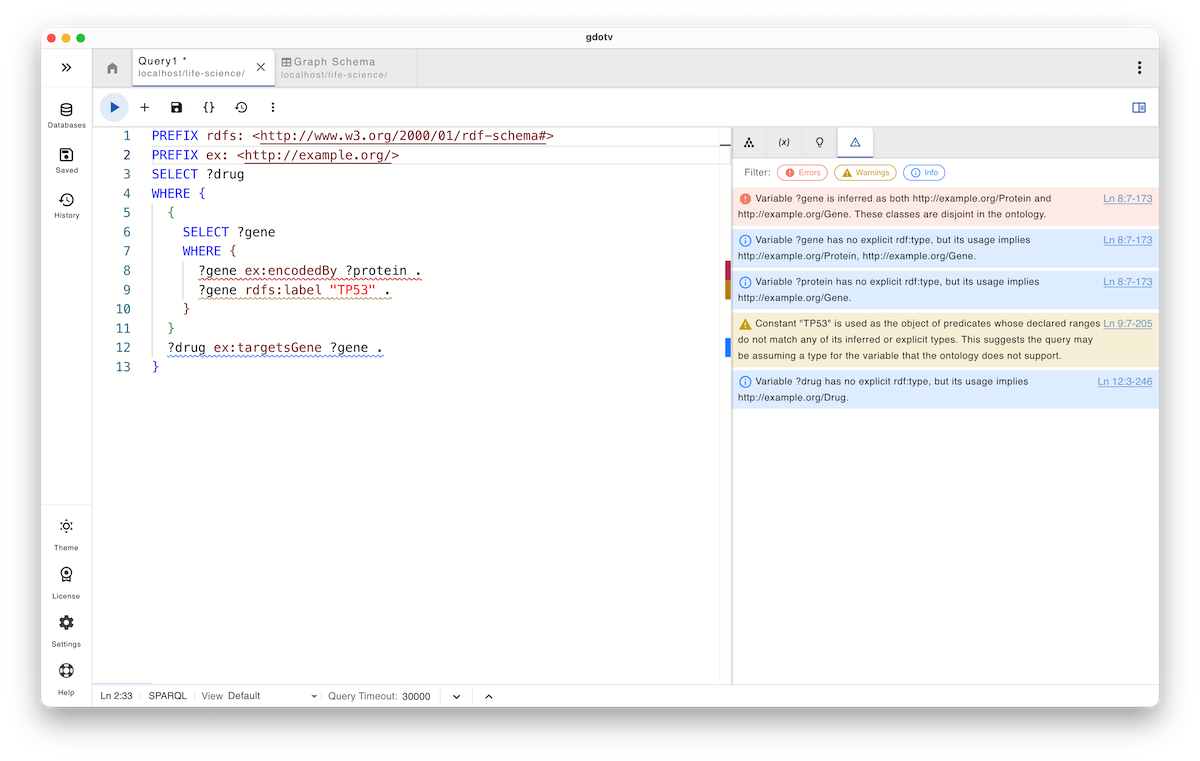

Pipelines & Name-Based Semantic Drift

The following query is syntactically valid and executes without errors on any compliant SPARQL engine:

SELECT ?drug WHERE { { SELECT ?gene WHERE { ?gene ex:encodedBy ?protein . ?gene rdfs:label "TP53" . } } ?drug ex:targetsGene ?gene . }

At first glance, the SPARQL query appears reasonable. The subquery returns a resource labeled "TP53", which is then treated as a gene and joined against drugs that target it. In practice, however, the subquery resolves TP53_Protein, a protein, not a gene.

This is where the danger lies. The predicate ex:encodedBy has a Protein-to-Gene domain/range definition, not vice versa, but because both entities share the same label pattern, name-based matching offers no protection. The subquery hides this ambiguity, and the outer query blindly assumes gene semantics for the variable ?gene.

As a result, if a drug in the dataset targets a protein rather than a gene (which is common in real-world life sciences data), the query will still return results. This again is not a syntax issue but a semantic drift. The query silently mixes genes and proteins, returns biologically invalid results, and makes it difficult to detect where the problem lies, at least for non-expert reviewers. This is a textbook case of name-based semantic drift.

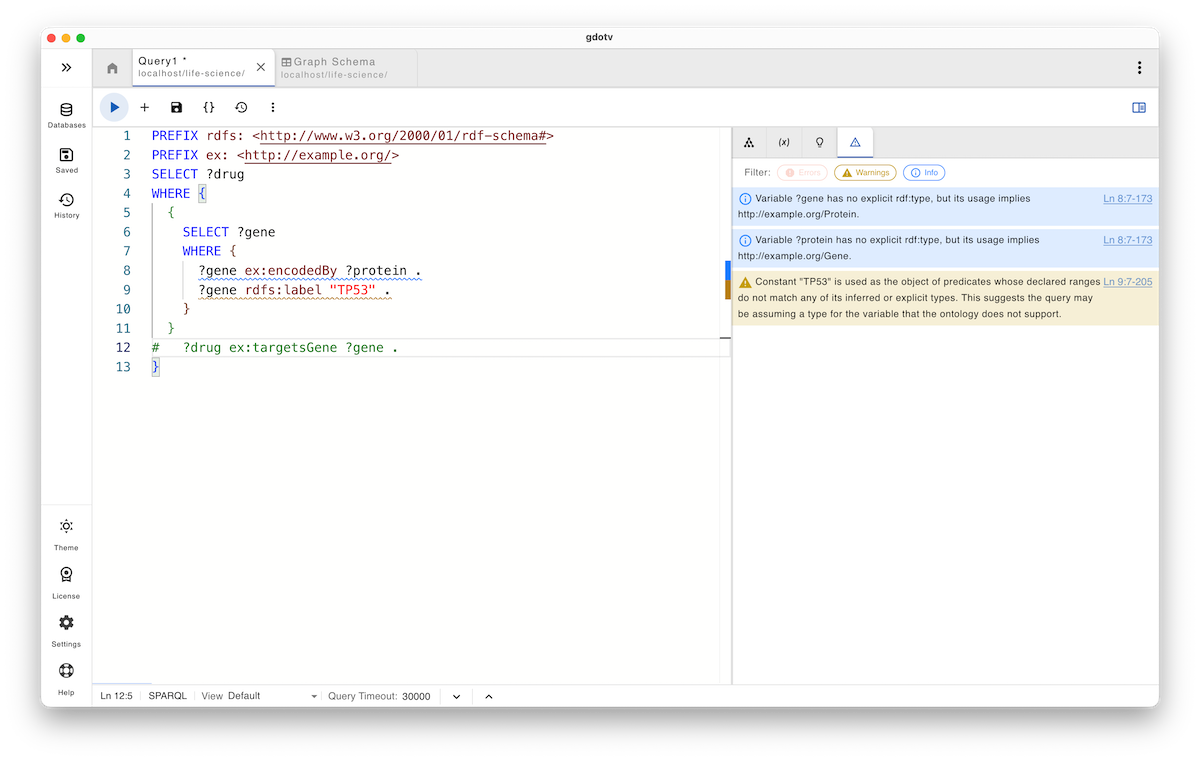

Query guardrails detect this situation by combining ontology knowledge, variable role inference, and scope analysis. The system infers that the variable ?gene is simultaneously used with both Protein and Gene semantics, and issues a strong warning as these classes are explicitly disjoint in the ontology.

Note that even without the ex:targetsGene pattern, the system still provides useful guidance, allowing us to identify that ?gene is inferred as a Protein, while ?protein is inferred as a Gene.

Based on this information, you are alerted to the conflict and can decide how to correct the domain and range usage before the query is executed or propagated downstream.

Conclusion

These SPARQL examples are deliberately small and focused, but the underlying issues they illustrate are widespread.

Similar semantic pitfalls hide in virtually any SPARQL query, often buried deep inside larger patterns, subqueries, or property paths. Even for experienced RDF practitioners, these problems are easy to miss because the queries remain syntactically valid and appear reasonable at a glance.

In this context, having a second set of eyes that continuously checks semantic consistency is not a luxury but a necessity. Query guardrails provide that semantic review layer, helping professionals catch subtle but impactful issues before they propagate into production systems.

Editor’s Note: SPARQL query guardrails are a feature of the forthcoming gdotv release, which is expected in the third or fourth week of February 2026. If you’re reading this blog post before then, sign up for the gdotv newsletter to be notified once the release is live!

Want to do more with your RDF data? Try out gdotv today and experience an IDE built for ontologists and RDF practitioners to help you query, explore, and visualize your connected data.

![Cypher RETURN Clause: Selecting & Shaping Query Results [Byte-Sized Cypher Series] Cypher RETURN Clause: Selecting & Shaping Query Results [Byte-Sized Cypher Series]](https://gdotv.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/return-clause-byte-sized-cypher-query-langauge-video-series.jpg)